A few weeks ago, in the post about setting, I shared with you a mnemonic I used with my students to help them remember the important parts of a story: Cows See Pretty Sunflowers.

Cows = Characters

See = Setting

Pretty = Problem

Sunflowers = Solution

All these things are necessary to have a good story. Today, we jump into the third point. So let’s get Pretty.

Let’s say I write a story about my morning. I woke up, ate breakfast, and had coffee while I read blog posts. You could even say my morning consisted of little stories. I wanted coffee, so I went to the kitchen and made coffee. Goal met.

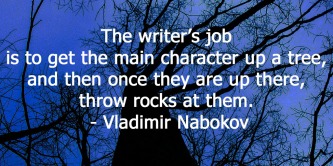

But that would be boring as hell. Sure, I technically had a non-coffee related “problem,” but there were no obstacles (or rocks, if you will) keeping me from solving it (Dan gives a nice description of how obstacles serve a story in this post). No obstacles = no story. Also, a goal =/= a problem.

But that would be boring as hell. Sure, I technically had a non-coffee related “problem,” but there were no obstacles (or rocks, if you will) keeping me from solving it (Dan gives a nice description of how obstacles serve a story in this post). No obstacles = no story. Also, a goal =/= a problem.

A story usually involves a character with one big goal, which may or may not be obvious to the character in the beginning. The big goal can also change as the story progresses. The story lies in how the character works to achieve the goal. Along the way, there are smaller goals leading to the big goal.

Maybe in our story, Bob’s big goal is to win a robotics tournament. But he can’t do it alone, so first he has to convince the guy who builds cars to help him with the mechanics. His smaller goal is to get Car Guy on board.

But remember, achieving goals alone isn’t a good story. I didn’t consider my lack of coffee a problem. But if my coffee pot malfunctioned and spilled hot water and grounds all over the counter, that would be a problem. Now I have a mess to deal with and still no coffee.

Maybe in our story about Bob, Car Guy was just released from juvie after beating up his neighbor. Bob doesn’t want to talk to him, but he’s the best at what he does. If Bob wants to build a contest-winning robot, he has to overcome his fear and probably convince Car Guy to work with him because Car Guy hates everyone. Those are two problems standing in the way of Bob meeting his goal.

The more rocks you throw at the characters as they work towards the goal, the greater potential for tension and a page-turning plot. But the types of rocks you throw matter. Consider the following questions:

1. What problems can the characters cause?

Characters are good at getting in their own way and in each other’s way because they, like us, are human – probably. But even if your characters aren’t human you’ll have to weave in some human-like qualities or your readers won’t be able to relate.

Humans make bad choices. They speed in traffic and eat too many cookies and act like jerks on the internet. They misjudge situations and act inappropriately. These facts are all story-telling gold.

2. Can the setting offer any obstacles?

Is the weather crappy? Is the building abandoned and ready to collapse? Is there enough food and water? Depending on your genre, setting can be a rich supplier of problems. But be careful not to make it the only source of obstacles, or the story starts to feel contrived and readers will question the intelligence of your characters.

3. Are the problems occurring organically?

That means are they coming from within the story itself – it goes along with the end of question 2, because all-setting problems wouldn’t likely all be organic. Imagine Bob and Car Guy walking back from the store after a parts run, and things are going well, until it starts hailing on them. They run for cover, and a car skids out of control and they have to jump out of the way. As Car Guy is picking up the dropped parts, a flood rushes towards them!

See where I’m going with this? At this point, I’m just the author pelting my characters with tragedies that come from nowhere. It would be better if when the weather hit and they ran for cover, Bob slid into Car Guy and Car Guy got pissed and hit him. Because Car Guy has that history.

Remember the movie Apollo 13? There was the first major disaster, after which Tom Hanks concisely relayed to Houston that they had a problem. After that, a series of other failures occurred, all related to the initial disaster. Those were all organic problems because they tied to an earlier event.

For more information about tension occurring organically, check out this post in which I use Jenga as a delicious writing metaphor.

As we wrap this up, I want to ask one final question:

Are you drawn to perfection?

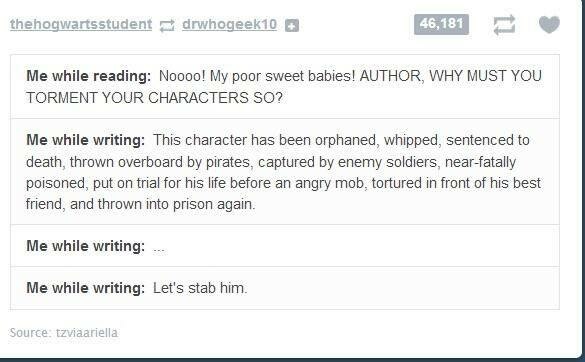

This is a common trait among new writers (myself included, when I was still cutting my writer’s teeth). We love our characters and only want good things for them. This means they are perfect people or bad things that happen aren’t really all that bad. This is story death.

As we develop, we tend to lean more this way (or I do):

The more problems the character faces, the more he has to overcome in pursuit of his goal. That makes the eventual victory (or not) much more satisfying.

What kinds of problems do you include in your stories?

Pingback: Does Every Story Need a Happy Ending? | A Writer's Path

Pingback: To Every Problem There Is A Solution – Or Is There? | Allison Maruska

I try to get rocks by the truckload for my stories. I love seeing CP reactions to them, too. It’s a guilty pleasure borne of pure sadism, I’m sure. Hopefully it makes the stories interesting for readers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It does! Keep chucking those rocks.

LikeLike

Oh poor fictional characters. They go through so much! But like you said, victory is all the more satisfying. I love Nabukov’s quote too. Very ironic yet probably one of the best bits of advice in the field.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have a CP who tells me when more rocks are required – just like that. This chapter could use another rock. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Anita Dawes & Jaye Marie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the reblog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on My Writing Blog and commented:

I love this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing with your readers! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

My character is in love with someone she can’t have because a) he is married to someone else, b) he is socially out of her league (a king in fact), c) he is in a different time. So first she has to find a way to get to his time, then she finds she likes his wife and so feels conflicted, but she helps the wife deliver her baby only to be blamed when she (the wife) gets poisoned.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooh, I love that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My main character has a strong aversion to religion…..so being the naughty writer I am, I surround her with religious people she can’t escape.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Perfect! I want to read it! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll let you know when it’s available!

LikeLiked by 1 person